Dr Susana Requena from the RSPB’s Centre for Conservation Science explains how new satellite tracking technology is giving us an insight into the life of the turtle dove.

Tracking and mapping

With continuing advances in tracking technology, our capacity to track birds keeps breaking new barriers. One species that has benefited from smaller tags and almost real-time satellite transmission is the globally-threatened European turtle dove (Streptopelia turtur), a widespread summer visitor that is now a global conservation priority with a decline above 30% since 2000 across Europe. In the UK, for every 100 turtle doves that there were in 1995 just six remain. Knowing more about their movements and ecology is a fundamental step in conserving this bird.

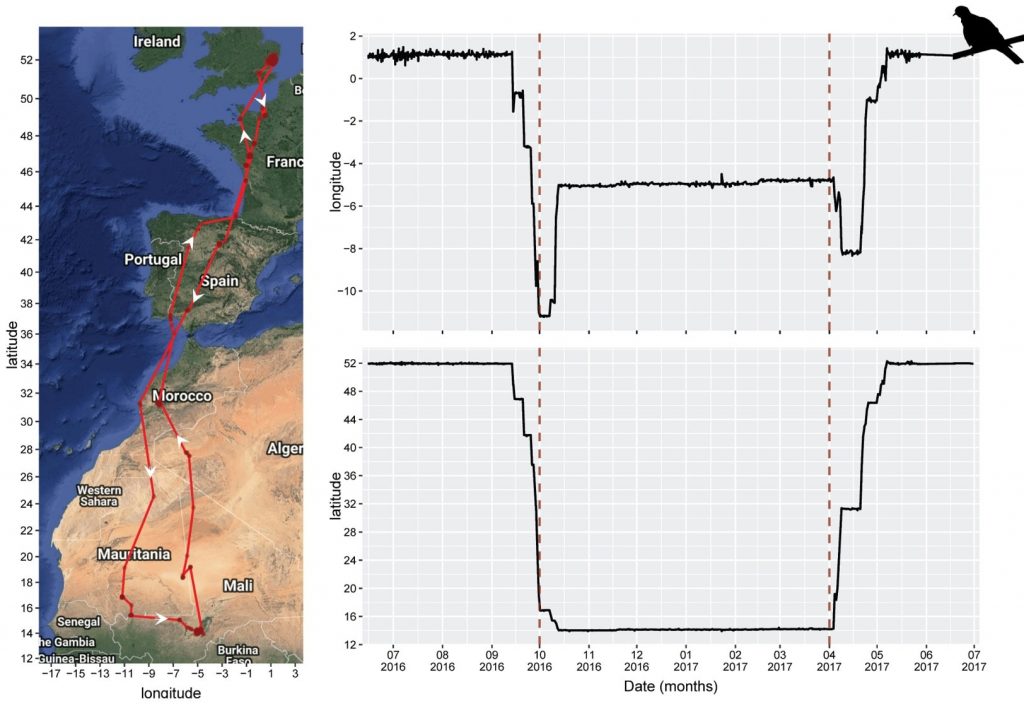

In 2012 we first fitted satellite tags to turtle doves to learn about their movements from their UK breeding grounds to their wintering areas. Subsequently, we have collaborated with the Office National de la Chasse et de la Faune Sauvage (ONCFS) in France, and now have data on 35 annual cycles from 28 birds: 12 tagged in the UK, 12 in France and 4 in Senegal. This valuable dataset is showing us how birds use their home ranges, both in the breeding season in Europe and on the wintering grounds in West Africa. We are learning about the routes they take between Africa and Europe and detecting important stopover sites where the birds rest along the way and the exact time at which this all occurs. Among different data processing and statistical analyses, we have also produced an animation of the tracks, so our numbers can come to life!

This is the story of a year in the life of our satellite-tagged turtle doves.

Credits: Susana Requena. Sources: RSPB, ONCFS, Mapbox, moveVis.

A long and hot… winter

Winter is seriously hot immediately south of the Sahara, where our tagged turtle doves spend around 200 days distributed across the floodplains of the Senegal, Niger and other rivers in Senegal, Gambia, Mali and Mauritania. Here, temperatures from November to March regularly exceed 30°C.

The birds’ home ranges in Africa are centred on a roost site, usually a large clump of trees, often thorny Acacias, which offers protection from predators. From here, birds will travel several kilometres each day in search of water and food, foraging in nearby farmland or natural grassland. They often rest during the midday heat and return to roost in the late afternoon.

As the landscape becomes increasingly dry as the season progresses, and we move into April, our turtle doves build up their fuel reserves, preparing for their long-haul trip north.

A fast journey to the north

After a few months of only local movements, life accelerates as birds hasten to return to the breeding grounds and establish a territory. Our turtle doves set off on a series of nocturnal flights and daytime rest-stops, that will eventually take them to their northern breeding grounds.

Their first big hurdle is the Sahara Desert and its sandstorms. Several of our tagged birds have perished on this first leg of the journey, while others have been forced to make a U-turn and wait for more favourable conditions. Most of our tagged birds made the desert crossing successfully, reaching Morocco where they stay for one to three weeks, resting and refuelling, before crossing the Mediterranean Sea to Europe.

Over the next week or two, the birds will travel through Spain, where some make a second stopover, and into France, the final destination for some of our birds. Others, continue north for a few more nights until they reach the UK, returning to the same territory they left behind the year before. All in all, the journey takes between 20 to 25 days to complete around 4,800 km.

The short, fresh …and busy summer!

When our birds arrive on the breeding grounds in early May, they have to face possibly the coldest days of their year. However, they need to get into breeding-mode soon after arrival; in the UK the first clutches are laid by the first week of June. With any luck, these are followed by a second and sometimes even a third breeding attempt, although these have become rarer in recent years – one of the reasons for the species’ population decline. Successful breeders generally stay in the UK until the end of August and into September, a total of about four months or only one-third of the year.

…heading south!

September is the month when we bid farewell to many of our summer visitors. In common with most other migratory birds, autumn migration among turtle doves takes longer than in spring, lasting about 31 days (in a range from 23 to 40 days) to travel approximately 5,000 km. They don’t need to reach the wintering grounds quickly, as the birds need to recover after the demanding breeding season, with their job done.

UK-breeding birds head south through western France, crossing over the Pyrenees and into Spain when the legal hunting season is already open in these countries. The birds need to refuel, so they stop over in the Spanish countryside and often stay there for one to two weeks.

Then they cross back over the Mediterranean Sea to Morocco. Not hanging around as they did in the spring, they pass into Mauritania, heading towards the Senegal river valley, now at the end of the rainy season, to a lush, green landscape and the prospect of another long, hot winter.

In one year any of the turtle doves tagged in the UK has travelled around 12,000 km (10,000 km for those birds breeding in France at l’Ile d’Oléron). Over one year they will have spent most of their time in Africa (54%), nearly one third in the breeding grounds (30%) and less than 20% migrating.

Natural and human-induced mortality takes its toll across the annual cycle. Natural events such as adverse weather and predation play a role, as does habitat degradation both in the breeding and wintering areas (reducing the availability of food, roosting and nesting sites), loss of suitable places to rest and hunting on migration. Our science is helping us to understand these problems and to develop and put in place the necessary conservation measures to combat them and ensure we can continue to celebrate the arrival of these birds in spring for many years to come.

Acknowledgements

RSPB: John Mallord, Guy Anderson, Joscelyne Ashpole, Nigel Butcher, Carles Carboneras, Tony Morris, Chris Orsman and Juliet Vickery.

ONCFS: Herve Lormee, Cyril Eraud, Luc Tison, Hervé Bidault and Marcel Rivière.

Many thanks to all those that contributed with their fieldwork in the UK, in France and in Senegal, landowners and communities and helped us funding these projects.

moveVis: Movement Data Visualization. R package version 0.10.2. GitHub and remote-sensing.eu

Movebank: archive, analysis and sharing of animal movement data. Hosted by the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology.

ONCFS